My readers, you asked brilliant questions the other day when I begged invited you to do so—when I asked what you’d like to know about mental illness and/or my experience of it. You inquired about everything from definitions and diagnosis to issues of stigma and medication management. You even asked if maybe I missed the illness, at least the manic highs, and if taking medication made me feel less authentically myself.

I can’t thank you enough. Your questions did exactly what I hoped they would—they got me thinking about my illness in new ways, allowed me new insights. You’ve provided a great list of issues for me to cover in future posts.

However, the clear place to start, in answering these brilliant queries, is with Lisa’s request for background information on bipolar disorder—issues of definition and diagnosis. (To check out Lisa’s blog, “Notes from Africa,” click here.)

Perhaps, one way to approach this background is to personalize it—to explain how my diagnosis came to be—a long story, but at least the first part will help define a few important terms.

I was hospitalized two times in the summer of 1989—very brief stays of less than a week each. At the time I was teaching English at Oral Roberts University and was an inpatient at the university hospital. Each stay was, unfortunately, a waste of time and money, as nothing was accomplished diagnostically.

In the spring of 1990, I was again hospitalized, this time twice in close succession, amounting to a total of 6 weeks or so in an in-patient psychiatric facility.

At this hospital I received the diagnosis that has stuck for the better part of 20 years. I have had other diagnoses along the way, as accurate diagnosis is a complicated process, especially for someone like me who has an illness that can mimic other disorders.

At any rate, in the spring of 1990, I was officially diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder—what was later determined to be a bipolar type of that illness. I don’t use the term “schizoaffective” very often, as it’s one most folks don’t know—though they understand “bipolar” fairly well. But, since we’re talking definitions and diagnosis today, this is an opportunity for me to clarify.

I like to think of mental illness the same way many clinicians do, as existing on a kind of continuum, with schizophrenia on one end, bipolar disorder (followed by major depression) on the other, and schizoaffective disorder in the middle. Basically, “schizoaffective disorder-bipolar type” means that I have symptoms of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (what some know as manic-depressive illness).

Schizophrenia, considered the most extreme psychiatric illness, usually begins in early adulthood and is characterized by symptoms such as confused thinking, delusions, and hallucinations. Technically there are 5 kinds of schizophrenia, two of which are well known—the catatonic and paranoid types.

Bipolar disorder, an illness that is marked by dramatic and unpredictable mood swings, is usually diagnosed in women in the mid to late twenties, though slightly earlier in men. Like schizophrenia, there are 5 kinds of bipolar disorder:

Bipolar I—usually considered the most extreme, as the patient has at least one full-blown manic episode.

Bipolar II—similar to but less debilitating that type I, this type never experiences a full-blown manic episode—only hypomania, a mania that does not include psychotic delusions.

Rapid Cycling—unlike types I and II, whose episodes of mania and depression can last months or even years, someone with this form of the disorder can swing between mania and depression several times in one week or even a day.

Mixed—a patient with this form of the illness can experience both manic and depressed symptoms at the same time—for example, the agitation of mania with a mood that is depressed.

Cyclothymia—a milder form of bipolar disorder than any of the others, it is marked with mood swings that are much less severe.

Patients with schizoaffective disorder have the symptoms of both schizophrenia and a mood (affective) disorder and will usually be diagnosed with one of two types—the depressive or bipolar kind. While the depressive form of schizoaffective disorder has symptoms of both depression and schizophrenia, the bipolar type is marked by the symptoms of both schizophrenia and bipolar I.

The bipolar type of schizoaffective disorder is more difficult than many other mental illnesses to both diagnose and treat, since it has symptoms that overlap with those of other psychiatric disorders. It can look like (depending where a patient is cycling at the time) schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, borderline personality disorder, even multiple personality, disorder when the patient is cycling both rapidly and extremely.

For many this illness can take a long time to diagnose accurately and even longer to correctly medicate, since doctors have to treat a number of different problems. For me this has meant a cocktail of medications that can manage 4 sets of symptoms:

Disordered Thinking (schizophrenic part): as manifest in delusions or hallucinations. These are treated with antipsychotic medications. I take a low dose of Risperal.

Mood Imbalance: as treated with lithium or an anticonvulsant such as Depakote or Neurontin. I actually take a high dose of Neurontin.

Depression: I take two antidepressants—Welbutrin and Prozac—that target two different neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that help to carry electrical impulses across synapses (space between cells) in the brain.

Mania: There are no specific drugs to treat mania, but in someone with a form of bipolar disorder, doses of antidepressants have to be managed and adjusted, so as not to trigger a manic episode. Doses have to be high enough to alleviate depression but not so high as to trigger mania.

Certainly, I could provide much more background information, but I also don’t want to burden you with more information than might interest you. However, in addition to defining various forms of mental illness, I should also mention that my illness, though symptomatically well-managed, is not curable.

I experience what are called “breakthrough symptoms” quite regularly. These are ones that do exactly what you might think—they penetrate the defenses erected by my medications. They spill over. And even though this might be happening to me, you likely wouldn’t recognize it, unless you knew me quite well. I’ve learned to ignore these periodic hallucinations. They irritate; they can make it difficult to concentrate. But they don’t prevent me from leading a fairly ordinary and productive life.

My biggest and best defense against these kinds of symptoms, however, is stress management. The more stress, the more breakthrough symptoms. This means eating healthy meals, getting plenty of exercise, maintaining a regular sleep schedule, and managing conflict successfully. It also means knowing what stresses me most, what triggers my symptoms and trying to manage that stress with extra vigilance.

I specifically require an unusual degree of predictability in my life. I don’t do well with sudden change, change that I’m not able to anticipate.

However, as many of you know, my partner Sara works in disaster response. (Because of that we’ve spent the last two years living outside the US and have only in the last month come home to Kentucky after a year in Vietnam and more recently another in Haiti.) Well, the thing about disasters is—not only are they, well, disastrous, but they also, for whatever reason, refuse to schedule themselves well enough in advance to suit my sensitive brain chemistry. Damn disasters!

But that’s probably the topic for another post, on another day.

In another couple of months, when Sara’s well-deserved break has ended, she’ll be reassigned to another disaster, and we’ll find ourselves somewhere else in the world. But given my brain’s place on the continuum of crazy, let’s pray we know where well enough in advance to avoid a psychiatric disaster of the Kathy kind!

Good post – a nice, clear and concise explanation! I was going to still ask about a bipolar continuum – but you’ve already answered my questions for me.

Thanks for the mention! 🙂

LikeLike

You are so welcome, my friend. I’m glad you asked, as I think the answer lays a great foundation for what’s to come. I know I can always count on you and your inquiring, South African self! Thanks so much for the question!

LikeLike

Great post! Thanks for the clear explanation. It leads me to another question which may or may not be important (feel free to ignore it). How did you meet Sara and what role has your relationship played in helping you deal with your symptoms?

LikeLike

Great question, Lisa! I’ve been with Sara for 5 years. We didn’t meet unitl I was looking pretty normal. I was working as an artist in residence here in Lexington and had just bought my home downtown. I don’t know that Sara has changed the way I manage the symptoms–except that loving her motivates me more than ever to keep the illness under control–as to be sick means pulling away into my own crazy space–away from her and the life we have built together–not literally, but emotionally. On the other hand, our lifestyle and her work are stressful, so I think I’ve learned to manage more stress and different kinds of stress–gotten better with a lack of predictability. Actually, this is worth exploring in a post of its own. Thanks for this quesion, Lisa!

LikeLike

This was good, Kathy. My guess is that many of us can recognize someone we know in your post. My aunt, an ex-boyfriend, the daughter of a close friend: I see pieces of them as I read. And I see how getting an abolute diagnosis and the correct meds can be difficult.

LikeLike

It’s insanely difficult–no pun intended. I don’t know how most people do it. Our healthcare system sucks in this country and our options for the mentally ill are abysmal. This is why most folks never really recover–are never again able to live “normal lives.” It’s sad! Sometimes I look back in disbelief at where I was and where I am today–not exactly sure how I got here, how I managed to regain at least this semblance of “normalacy.” Hope you have a great weekend, Renee!

LikeLike

Pingback: A Continuum of Crazy | reinventing the event horizon : Schizophrenia Page

Thanks for this really clear outline of bipolar disorder I had no idea there were so many nuanced defintions. It’s so interesting why some people get this illness and some people get other illnesses – diabetes, for example.

LikeLike

It’s kind of fascinating–isn’t it. There is some serious science about how to understand this and other psychiatric illnesses! I hope it provides a solid foundation for things I’ll explain later. Thanks so much for commenting. Take care, Jacqueline!

LikeLike

Thanks for laying the info out in easily-understood form, Kathy! I too had no idea that there were so many forms of bipolar disorder.

Looking forward to another “chapter.”

Hugs,

Wendy

LikeLike

Thanks, Wendy. Most normal people wouldn’t know this, but I think it provides a nice background/context in which to place the story itself. I’m glad to hear it was easy to understand. I was afraid the explanations were becoming too tedious. Glad it was helpful!

LikeLike

This post showed me I have a whole lot to learn. You, my dear, are helping me! Thanks for this post!

LikeLike

Actually, 99% of people in North America wouldn’t know this. Either one knows this because they are a professional in the field or because they have a loved one with the illness. I just know because i like to understand what’s wrong with me. I found I was better able to contribute to my own recovery by understanding objectively what was wrong. Take care, Tori!

LikeLike

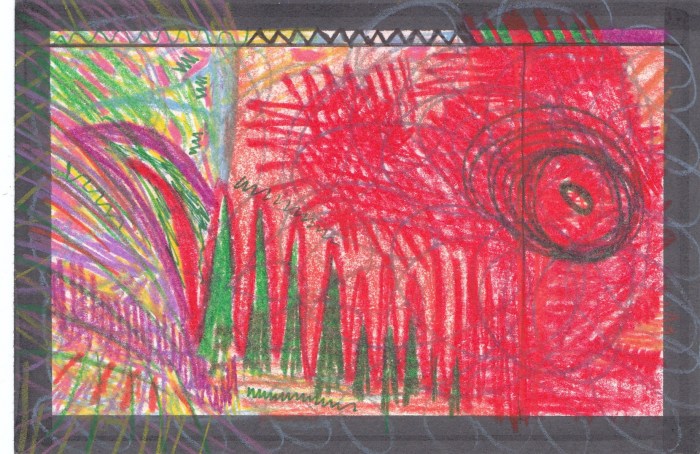

An excellent post and once again you drawing/paintings provide another perspective of the issue.

LikeLike

Thanks, Charles. The first piece today was pretty raw and primitive, but I thought it communicated something about the chaos I was experiencing at the time. Take care, my friend—————-

LikeLike

Thanks for such an orderly and insightful summary of bipolar disorder. I have several friends with similar diagnosis, but I’m ashamed I never took the time to ask them to spell it out for me.

Here’s what I want to know: Your move back to Lexington was a sudden one. Even though you went back to a city and home that are familiar to you, how well did you cope with the change?

LikeLike

Great question, Maura. It was sudden, very sudden and unexpected. I think Sara was more concerned about my ability to adjust than I was. I had so hoped to spend more time writing about Haiti; we hadn’t anticipated leaving for at least another year. However, I have adjusted well. I’m just grateful I had begun moving the blog in this direction before we learned what was happening. Otherwise, I would have been lost. I at least knew that I had alot of work that I could really only do from here, so that, I think, has helped with the transition. I don’t know if that makes sense. But, yes, Sara was concerned that it might be difficult. I do pretty well when I have a plan and having ironically laid out a plan just days before we got the news helped me have something to fall back on.

Take care, Maura. Hope you have a great weekend!

LikeLike

You are a very brave woman!

Art is beautiful!

LikeLike

Thanks so much. But is one really brave for living a life you have no choice about? I don’t know. Thanks so much for reading and taking the time to comment. I hope you’ll come back!

LikeLike

Ooohh… a cliffhanger! I am fascinated about the dynamics between your need for predictability in life and Sara’s career in disaster response! I am a homebody myself, and I don’t know if I could handle the sudden moves across the globe that you two have to negotiate as a matter of course– and that’s WITHOUT bipolar disorder. I’d like to read a whole post (at least!) about the interplay between your need for routine and how you manage a decided lack of routine in your partnership and lifestyle.

This was a great post as well- very informative!

LikeLike

I wish it weren’t a cliffhanger–would do anything to know–to even be there already, where ever there is. It’s actually a good idea to do a post on this issue of predictabiity and the decided lack of it in my life–even though I thrive on it. I will do one. I just don’ really understand how we make it work. I will have to think about this. Thanks for sharing your interest in this, Dana.

LikeLike

So painful. My most favorite aunt and one whom I adore suffers from untreated bipolar. She’s a raving mean mess now. It just breaks my heart. Having been involved on the pharma side with a drug treatment it is also sad to see how difficult it is to treat due to people taking medicine, getting better, then going off thinking they’re no longer needed, only to spiral down again. Kudos to you for recognizing your triggers, keeping up a lifestyle that you know is good for your health, and for staying on your medication. I wish my aunt would follow your example….

LikeLike

I’m so sorry about your aunt! My great, great Aunt was also ill her entire life–before the days of psychopharmacology. The family kept a private nurse for years, so they could keep her out of an institution. But refusal to take medication is common, or at least not uncommon, in bipolar disorder. Folks adore mania, and rightly so. Also, antipsychotic drugs, even the new generation ones, can make you feel bad, drugged, dull. It must be tough for your family. Take care, my friend!

LikeLike