I’m a wanna-be artist, a sort-of, almost artist—certainly not by training and clearly not because of craft.

I’m also an artist who has struggled with bipolar disorder, someone who appreciates the creativity that is often an unexpected gift accompanying the illness. I’m someone who has not only made art when I was sick, but continues to create even when I am well, as an outgrowth of recovery. In the art world I’m what would be called an “outsider” artist. I don’t always know what I’m doing. I just do. Art.

I’m also a writer and artist who has lived in Haiti for the last year with my partner. Sara has directed an international NGO’s response to the earthquake. But we are preparing to go home next week, and I’m thinking not only about what Haiti has given me, the gifts I will take home, but also what I’ll leave behind.

Indeed, one of the gifts I’ve given is a large piece of art, one I created for Sara’s NGO from a throw-away piece of furniture—a huge serving bar I painted last summer.

The bar is nearly 9 and a half feet long and lives on an upstairs patio at Sara’s office in Port-au-Prince.

It was white, ugly, an eye-sore, really. But Sara wanted to save it. She thought it, like Haiti itself, should be given a second chance at life, that the bar could be used for receptions, to serve meals on special occasions. She thought I was the one to midwife this rebirth, that I was the one to take on the task, that as someone who has repurposed art as part of my own recovery, I could gift a born-again bar to the wonderful people who work here.

I loved the idea and took on the project enthusiastically, in the end creating a mixed-media piece—one that incorporates the organization’s logo in strategic places, as well as decoupaged-maps of Port-au-Prince and each location in Haiti the organization works.

I also included stories from the local newspaper, highlighting big events in the news during the months after the earthquake.

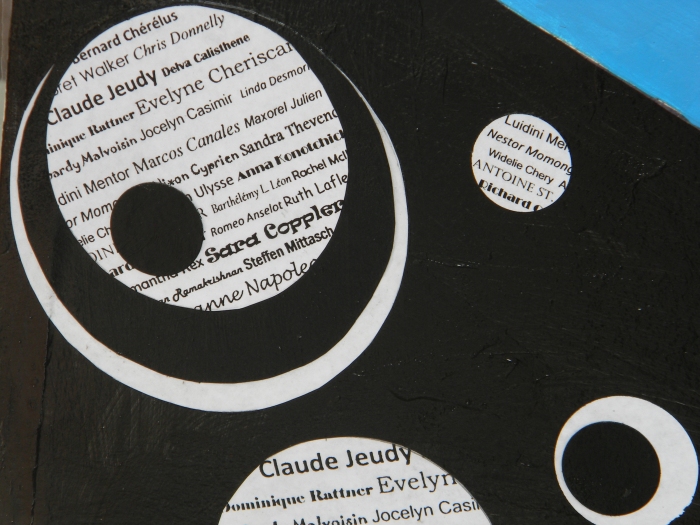

I included text from the organization’s 6-month, post-earthquake report, as well as the names of almost all the people who had worked on the NGO’s reconstruction effort—folks from more than a dozen countries around the world.

The front of the bar repeats the organization’s logo above each flower petal:

As well as the names of staff in black and white circles:

The top of the bar includes the maps and newspaper text:

However, soon Sara and I will leave Haiti; soon we’ll leave the places mapped on the bar-top at a bit of a distance, at least geographically.

And though we’ll leave when the organization’s work here is still incomplete, though in many ways it seems too soon, I’ll leave a piece of myself behind, one that I hope will serve the NGO’s mission here well into the future. I’ll leave not only a piece of my art, but also a piece of my heart, knowing this is not really an end. We leave but others will come.

Haiti has taught me this lesson: that indeed good things can come from our departure. It has taught me not only how to birth a new bar, but also how to hope, how to see potential in seeming destruction, how to dream a new dream, how to hope a new hope. It’s reminded me that, if art can come out of sickness, then indeed beauty can come out of the earthquake’s ruin.

I believe that in every beginning an end is waiting to happen and from every illness or devastation a new beginning will grow.

Peace to people of Haiti—

And thank you!