In 2011, it’s hard to know which is weirder—watching myself on videotape narrating my psychiatric struggle in 1997 or knowing now how inherently different my life is 14 years later.

Though ’97 was difficult, I generally had to fight hard for more than 10 years following my diagnosis with bipolar disorder in 1990, a decade of pain and endurance, as I struggled with every ounce of energy available, battled a diagnosis that doomed me to countless psychiatric hospitalizations and chronic poverty. I lived without a car and in 1997 on $736 a month.

Things were particularly bleak during the winter and spring of 1997, when I was hospitalized twice and struggled to complete even the most basic tasks of daily living—getting myself to and from treatment, feeding myself regular meals, taking medications as prescribed. I spent 5 hours a day on Dallas city buses, struggled to purchase groceries on $30 a week, and suffered so with memory loss, I couldn’t remember whether or not I’d taken the Zyprexa (an anti-psychotic drug) that dulled my thinking and left me listless, not to mention sleepy and ravenously hungry.

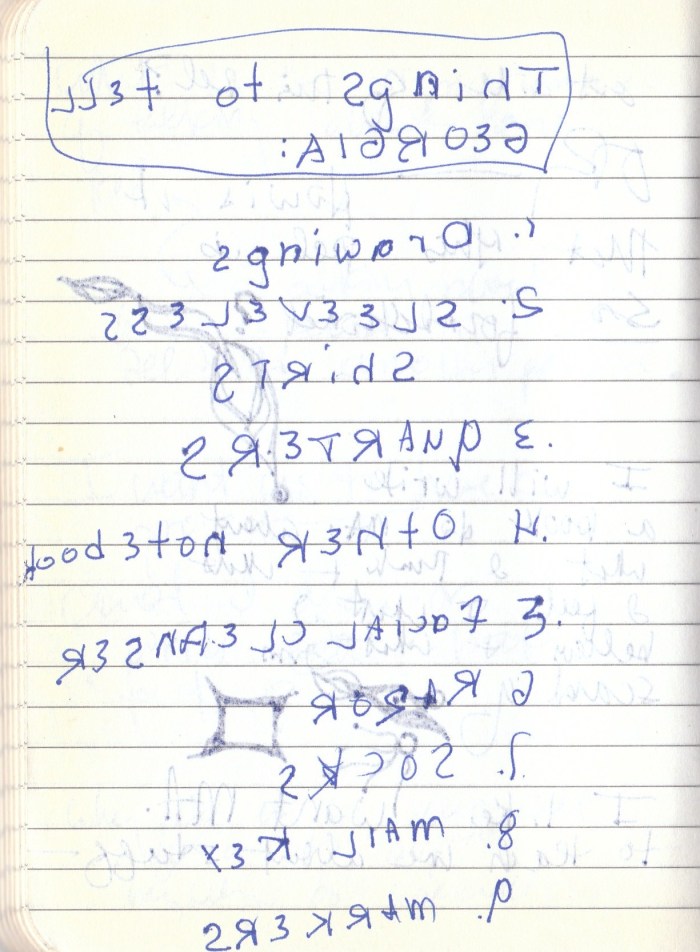

But yesterday, in the context of a memoir-writing project, I watched video-taped therapy sessions from 1997, a number of them, at least 6 hours worth.

I noted especially that on March 6, 1997, wearing red sweat pants and my hair in a loose bun, I congratulated my therapist on the occasion of her 49th birthday. I was 35 years old but looked at least 10 years younger than that—thin and toned as I pretzeled myself into a corner of black leather sofa.

But what I remember about that time, recall without having to watch a video, is the belief that my therapist was rather old—unimaginably older that I could ever imagine myself becoming.

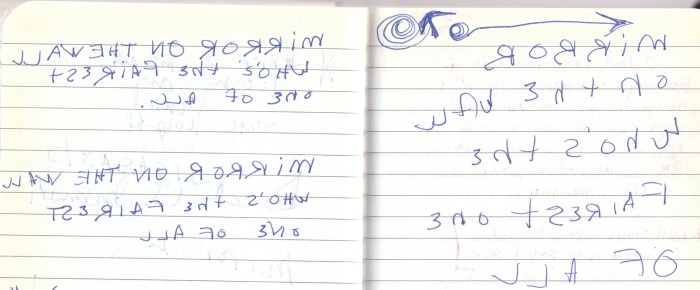

Yet now, in 2011, I am myself 49. I am the “old” I couldn’t imagine myself becoming. And this is a hugely strange experience— sitting in a home I own, with my graying hair and gained weight—watching a much younger version of myself, wishing a woman I so respected happy birthday, knowing I was thinking, “Gosh, she’s almost 50. I can’t imagine being that old.”

Not only am I watching myself 14 years ago—seemingly endless hours of myself frozen in time—but also I’m thinking about who I am myself now at this ripe old age—how different I look—how inherently reversed my circumstances are—how much better, richer, fuller my life is—how my experience is now what I only hoped it could be then, what I only dreamed it could be, but never expected it could become.

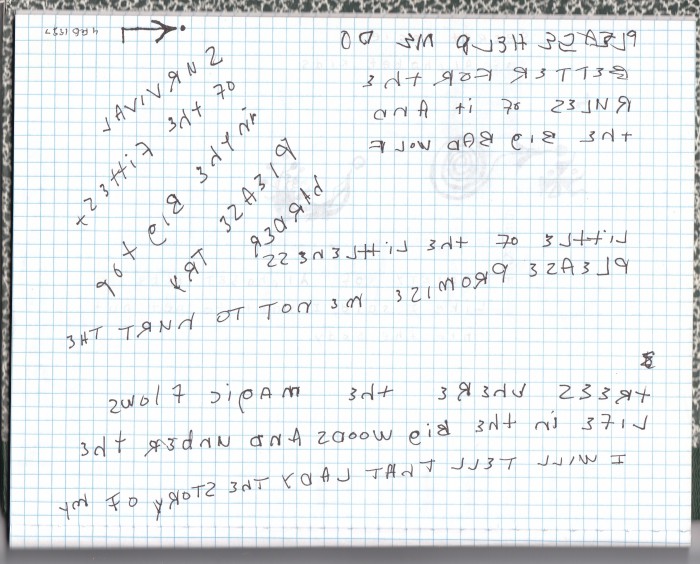

Clichéd as it sounds—I am now literally living a dream come true—a dream I articulated to my therapist in 1997—a dream about teaching at a university again, a dream about writing—a dream about succeeding—a dream about love.

I don’t know how it happened. I don’t know how or why I became ill, why my mind deteriorated to the point it could no longer be trusted, how it is that now I am well—at least in relative terms—my symptoms well-managed.

In 1997 Bill Clinton was just beginning his second term as president; scientists were cloning Dolly the sheep; and in the US we would soon have a balanced budget. Though Princess Diana and Mother Teresa died, it was a time of hope—a time of new beginnings and relative prosperity.

However, my memory at the time was so poor, my connection to the larger world so tenuous, I recall little of this. I know most of this from my more recent efforts to go back and fill in the blankness my brain experienced as real life.

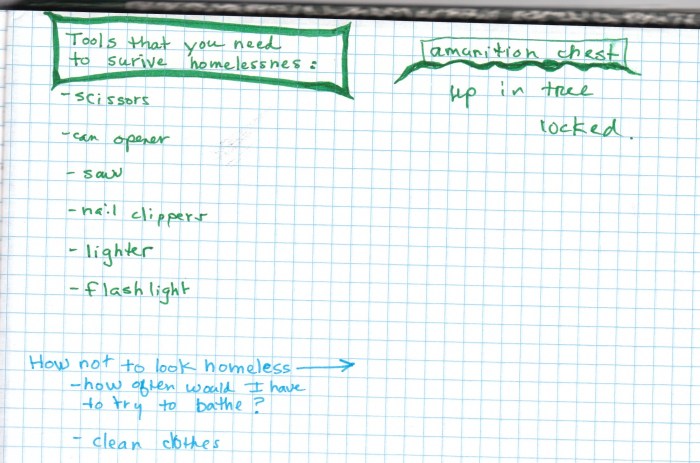

Now, as I watch these videos, as I reflect on how I felt 14 years ago, on how it feels now to not remember, I’m amazed that I have come this far. That I no longer fear homelessness, that I no longer live in government housing, that I now own a home, function well, love an amazingly accomplished woman who loves me even more.

How did I survive more than a decade of seeming defeat? How is it that I’ve recovered to this degree? How did this come to be, this tale of endurance, my narrative of hope? How is it that this stunning grace has happened?

I hope my memoir can help me share this amazing magic—let others know that what sometimes seems an illusion of recovery can indeed become a solid and shared reality—a Boomer’s madness morphed into dream-come-true.