I’m having a weird week–not wanting to write, not wanting to look back–a relatively wordless week, compared to most–a week without much in the way of memoir work, a week with fewer than usual over-the-shoulder glances.

In all honesty, I’ve had some break-through bipolar symptoms–ones that penetrate the protective barrier medication erects between me and my manic-depressive illness.

Sara says I’ve been manic. Though I’ve not noticed that exactly, I have felt like I was floating, like I’m hovering high inside my own head–the bulk of me shoved up above my left eye. I know that likely sounds strange but the physical sensation is nearly always the same–floating–hovering up and to the left.

My only wish is that this mania would bring with it the creative energy I used to have when my mood was on its way up.

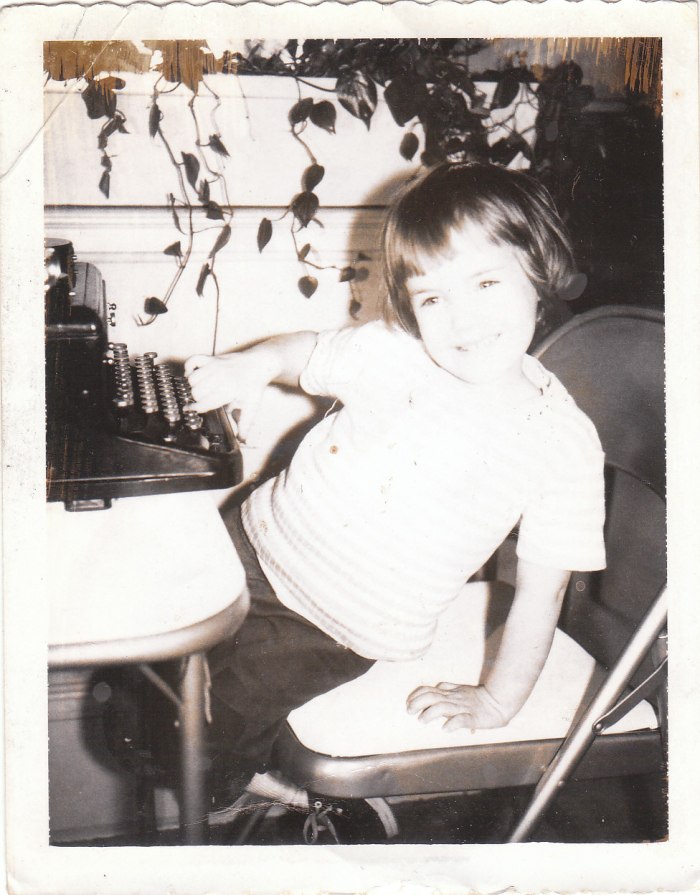

It used to be, when I was ill, creating felt effortless, as automatic as breathing, and I did it with the urgency and abandon of falling in love, deeply and maddeningly in love. I could no more not create than I could not now eat or sleep or dream of waking up tomorrow in a world with less poverty, less hunger, more rights for the mentally ill and anyone living near the edge, far from the center of the bell curve that is middle American comfort.

This week creativity has taken effort. It’s been labor-intensive and even exhausting. This week it’s required industry and diligence, determination, duty, drive.

But it’s better than it was when in the early ‘90s I began taking antipsychotic medication and the only ones around were things like Haldol and Navane, the older generation of drugs that made me feel even less like myself than I do now. Those drugs made me feel lethargic, zombied, and at times even, down-right dead. They made me feel thick-headed—like I had to swim through a fog to interact with the world. I had to fight to stay awake—to keep my eyes open—to carry on a conversation—to process language.

Then friendship felt nearly impossible–too much work to talk, to articulate, to move my mouth to form the words. The drugs blunted everything human about me—made me lose everything and anything I loved about myself, a woman with passion, a woman who cared intensely about the world and the people around her.

All that was gone—or at least out of reach—beyond the fog I couldn’t fight or navigate my way through–the fog that was dense, thick, terrible and deep.

But the newer drugs of the 21st-century are better. The medicated me of this decade is more alive and energized than the me of 10 or 20 years ago. Most of the time, I no longer fight the fog that separates me from the world.

Now I only fight an internal fog that keeps me, as it has this week, from the deepest and most creative places inside, from the art-making place in the center of my psyche. This week writing has meant managing this mist, hacking through the haze between me and the vibrant, secret center where the creative Kathy waits.

But she’s still there. And maybe next week she’ll be easier to find. Maybe then the two-faced, creative me–monstrous and magnificent, hideous and holy–maybe she won’t hide so deep inside.