I heard someone say the other day that home is where your story begins. It’s where we’re rooted, what grounds us in the present and gives us a history to remember.

I’ve been fascinated for years by the notion of place and the impact it has on who we become. I’ve even oriented my composition classes around questions of space and place, exploring how who we are is so often affected by where we come from.

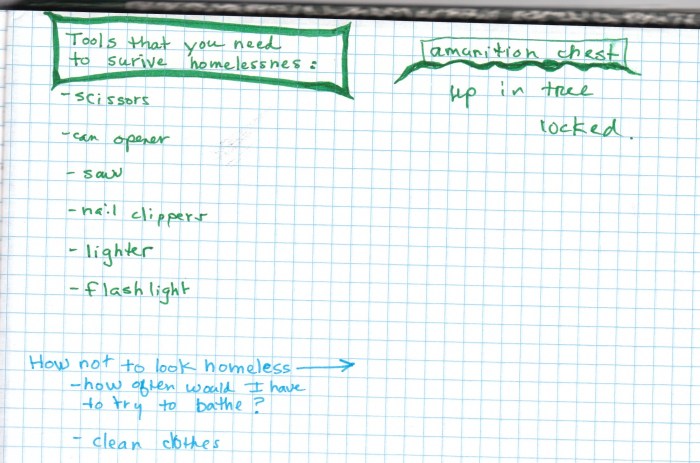

So it seems unsurprising then that I might orient my memoir about recovering from mental illness around similar concepts. I’ve posted pieces about fearing homelessness, about my inability to afford housing in any remotely comfortable way, about wanting the hospital to be my home. I even took this one step further yesterday when I mentioned now owning a home.

However, an important part of this progression toward home ownership involved twice living in government housing—not a lovely place by any means—but not the housing horror folks often expect.

In June of 1998, I moved into Lakeland Manor—a government-subsidized, semi-high-rise for the elderly and disabled in Dallas, Texas. I decided this move made sense when it became more and more difficult to afford the small, one bedroom apartment I leased on Northwest Highway. I scraped and scavenged each month to pay the rent, making myself abide by outrageously restricted spending limits that may have reinforced patterns of neglect and denial I carried over from childhood. The apartment at Lakeland Manor saved me more than $200 a month—what to me amounted to a small fortunate at the time. The year before, I had told my therapist that if I could only make $100 more a month, I would feel rich.

I’d gotten to know a woman who owned a home in a neighborhood near the complex, and visiting her home, I’d noticed the place was not-so-bad. In fact, my friendship with Jeanette impacted my decision to move, as I began to recognize the impact proximity might have on my recovery.

The Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex is not a small place. My apartment was far from my therapist’s office in Plano—an expensive place to live, and I knew how not having a car kept me isolated, if I didn’t have friends nearby. I had been fortunate to have my friend Ellen living in the complex on Northwest Highway.

I frankly adored Ellen. She was my friend from Tulsa, my first openly lesbian friend, one who had also moved to Dallas for treatment purposes. Ellen was witty, brilliant, creative—great fun to be around when she was sober or not psychotic. Unfortunately Ellen’s efforts toward sobriety left her more psychotic, more often, and in some ways less available.

My move from Northwest Highway to Lakeland Manor had no conscious connection to Ellen’s decline, but tragically Ellen died suddenly shortly after my move, having visited my new apartment on only one occasion. Ellen’s death devastated me. There seemed no clear medical explanation for her dropping dead one afternoon in the parking lot of the apartment complex where we had lived. But once Ellen was gone, I was relieved to have already moved. I don’t imagine I could have tolerated living there with her gone.

This issue of proximity made one friend I met at Lakeland Manor enormously important, as I finally had a friend who was bright and creative living in the same building. Elaine was a classical musician who played the French horn—an SMU grad who loved to laugh as much as I did. Elaine had had a stroke a number of years back, as well as a kidney transplant, so her physical disability qualified her to live in the building.

Elaine was a friend in every sense of the word. She was my age, came from a similar educational background, and was finally someone with whom I could socialize, without either transportation or finances being issues.

Except for Ellen, when I lived on Northwest Highway, none of my friends lived nearby. Without transportation in a city like Dallas—especially when you don’t live in a particularly safe part of town—it’s logistically difficult to go out with friends after dark. And given all the other battles I was fighting at the time, dealing with getting home after dark was more than I could manage—so mostly I stayed home.

However, I couldn’t afford to socialize either. I couldn’t afford movies or going out to eat or shopping—activities most folks not fighting poverty enjoy. This created a financial incongruity in almost every relationship—leaving me feeling isolated and alone.

With Elaine, all of this changed. Neither of us had any money—neither of us could afford to go out—but there were countless evenings when Elaine would come down to my apartment or I would go up to hers, so we could cook dinner together and watch T.V. The meals were simple. We ate lots of pasta.

I remember we spent Christmas of 1998 together. It was icy outside. We couldn’t go anywhere, but that didn’t matter. We were friends, and we were together. Ironically, I owed this friendship and the joy it provided to the fine folks at the Dallas Housing Authority.

So Lakeland Manor, government housing or not, was in many ways a relief to me, my apartment a retreat—a place I could finally comfortably afford. Plus, since the rent was based on income, I never really needed to fear homelessness again.

Home is where ones story begins, and the home I made at Lakeland Manor is one that ultimately allowed my recovery to take hold—grow roots—be strengthened. I gained confidence while living there. I felt good about myself and proud.

Yes, my apartment had roaches. It has linoleum tile on the floor. It was ugly.

But I worked hard to make it feel like home, and quite honestly I loved it, linoleum and all.

So, home is where one’s story begins, humble as that home may be.